The Role of Qualitative Research in Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

DATE

July 15, 2024

AUTHOR

Sascha | Co-Founder & CEO

Health technology assessment (HTA) aims to provide a comprehensive evidence base to inform decisions about which medical treatments, devices and health interventions should be adopted and funded within a healthcare system. While quantitative data from clinical trials and economic modelling is crucial, qualitative research is increasingly recognized as an essential complementary component of robust HTA.

Qualitative research employs methods like interviews, focus groups, observations and textual analysis to explore phenomena in depth – seeking insights into perspectives, motivations, contexts and the meaning people ascribe to their experiences. By giving voice to the lived realities behind quantitative metrics, qualitative inquiry can significantly strengthen HTA processes.

Understanding Patients’ Needs, Values and Preferences

A core aim of patient-centric healthcare is aligning care with patients’ own priorities and what they perceive as meaningful benefits. Quantitative clinical trial data tend to focus on investigator-defined endpoints like survival rates or biomarkers. Through dialogue, qualitative techniques can elucidate which specific outcomes related to symptom burden, functional status and quality of life domains (physical, psychological, social, etc.) are most vital from patients’ viewpoints.

The Patient Perspective on Clinical Trials – What’s Going Well, What Needs to Change?

Get the survey results to learn more about:

- Current barriers and patient access to trial participation

- Expectations around travel, on-site visits and communication

- Patients’ openness towards digital technologies in trials

The importance of patient input is now emphasized by major regulatory bodies. For example, the European Medicines Agency states that patient-reported outcomes reflecting how patients feel and function should be considered alongside clinical data when evaluating new therapies.

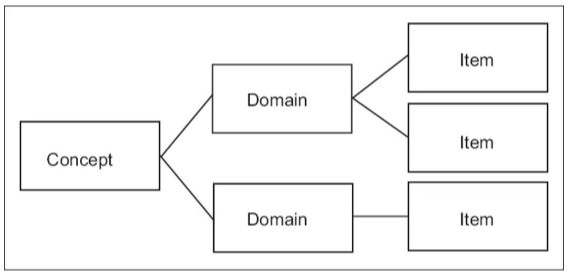

Identifying Meaningful Concepts and Outcome Measures

Building on understanding patients’ priorities, qualitative research can further guide the selection and development of appropriate patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and other instrument tools applied in quantitative studies. Formulating the right conceptual framework with relevant multi-dimensional domains and specific items/questions is critical for PROMs to effectively capture outcomes that are meaningful and applicable to a target patient population.

Qualitative evidence on patient language, perspectives and experiences is vital for avoiding measurement deficiencies where PROMs miss crucial aspects of patient experience or use items that inadequately reflect the intended concepts. Iterative qualitative methods can refine conceptual models and iteratively improve the content validity of outcome measures.

The major concepts measured in PROs

| Concept | Description |

| Quality of Life (QoL) | According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Quality of Life (QoL) is described as an individual’s subjective evaluation of their life circumstances within the framework of the cultural and societal norms they are part of and in connection with their personal aspirations, benchmarks and worries. The conventional measures of QoL encompass factors such as financial status, employment, environmental conditions, physical and mental well-being, educational attainment, recreational opportunities, social connections, spiritual beliefs, sense of safety and personal freedoms. QoL finds application in various domains such as global development, healthcare, governmental affairs and the workplace, indicating its broad relevance and impact. |

| Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) | Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) is a multifaceted concept that encompasses the patient’s assessment of how a health condition and its management impact various aspects of their everyday life. This includes considerations such as physical functioning, psychological well-being, social interactions, role responsibilities, emotional health, overall sense of well-being, vitality and general health status. HRQoL essentially evaluates the interplay between Quality of Life (QoL) and health, reflecting the broader implications of health on an individual’s overall life satisfaction and functioning. |

| Patient satisfaction (Reports and Ratings of health care) | Assessment of treatments, patient preferences, healthcare delivery systems, healthcare professionals, patient education initiatives and medical devices. |

| Physical functioning (disability) | Physical limitations and activity restrictions, including: self-care, walking, mobility, sleep, sex, disability. |

| Psychological state | Positive or negative affect and cognitive functioning, including but not limited to: anger, alertness, self-esteem, sense of well-being, distress, coping, feeling anxious or depressed. |

| Signs and symptoms (impairments) and other aspects of well-being | Reports of not directly observable symptoms or sensations, including: energy, fatigue, nausea and irritability. |

| Social functioning | Limitations in work or school, participation in community. |

| Treatment adherence | Observations of actual use of treatments. |

| Utility | Utility, often referred to as usefulness, denotes the perceived capacity of something to fulfill needs or desires. In the realm of health economics, utilities serve as metrics for gauging the intensity of patient preferences. For instance, they measure the significance patients attribute to different factors like symptoms, pain and psychological well-being. By assessing how new treatments influence these factors and consequently impact quality of life (QoL), their value can be quantified. This methodology is frequently employed by health technology assessment (HTA) bodies tasked with advising government health departments on the funding suitability of treatments. |

Explaining Variations and Contextual Factors

Even when quantitative studies demonstrate a treatment’s efficacy at a population level, qualitative methods can elucidate contextual factors and mechanisms that may drive variations in which individuals benefit most or experience different effects. Differences in attitudes, support systems, socioeconomic circumstances, cultural beliefs or other local realities can all shape if and how interventions succeed in actual practice environments.

For instance, qualitative inquiries could uncover attitudinal barriers or facilitators affecting non-adherence rates. Or they may shed light on how variations in provider-patient communication quality influence outcomes. Such intelligence is invaluable for anticipating implementation barriers and tailoring strategies.

Interpreting Health-Related Quality of Life Data

Many HTA assessments apply Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) instruments, which are multi-dimensional patient-reported measures evaluating how health conditions and treatments impact areas like physical functioning, psychological wellbeing, social interaction and more.

However, understanding what numerical HRQoL scores signify for patients’ lived experience requires qualitative context. Applying qualitative methods like phenomenological interviews can reveal the first-hand realities that quantitative HRQoL measures attempt to distill into scores. This grounds the interpretation of HRQoL data in the tangible perspectives and day-to-day impacts described by patients themselves. Without this interpretive layer, there is a risk of oversimplifying the profound effects of illnesses and treatments on human lives into just clinical rating scales.

Synthesizing Qualitative Evidence Systematically

While individual qualitative studies offer important contextual insights, techniques have emerged to synthesize findings across multiple qualitative studies through methods like meta-ethnography. By systematically integrating qualitative evidence alongside quantitative data following rigorous methodological approaches, HTA processes can construct more comprehensive and nuanced understandings to guide decision-making.

Qualitative evidence synthesis enable reviewers to address questions beyond just “what works” for a particular intervention. They can dig into explanatory factors of why and how interventions may work better in certain circumstances, apprehend key implementation barriers and center the lived experiences of those most impacted.

Conclusion

As HTA frameworks continue evolving to prioritize patient-centeredness, real-world impacts and societal value perspectives, the role of rigorous qualitative inquiry will become increasingly vital. By giving voice to the human realities behind the numbers, qualitative methods can help steer healthcare technologies and policies toward more optimally serving those they are meant to benefit across all backgrounds and contexts.

However, qualitative research should not be viewed as a panacea or replacement for quantitative methods. Its greatest value lies in complementing and enriching the scientific evidence derived from clinical trials, economic analyses and other quantitative approaches central to HTA. A balanced, multi-methodological evidence base is needed to make high-stakes decisions impacting population health and healthcare resource allocation.

There are certainly challenges in effectively incorporating qualitative data into HTA processes traditionally centered on quantitative evidence hierarchies. Developing robust methods for qualitative evidence synthesis, managing potential researcher biases and bridging different disciplinary perspectives and incentives between qualitative and quantitative experts remain works in progress. But the increasing emphasis on patient-focused benefit-risk assessment, health preference research and stakeholder engagement is driving impetus for HTA bodies to prioritize and refine their use of qualitative methods.

Ultimately, qualitative inquiry’s power to illuminate the nuanced contexts, human factors and lived experiences surrounding an intervention is an invaluable complement to quantitative data focused on measurable outcomes and average treatment effects. A comprehensive, multi-dimensional understanding is needed to ensure new health technologies properly account for the realities facing diverse patient populations and healthcare environments. Qualitative methodologies deserve a vital role in evolving HTA towards optimally informing healthcare policies and practices that improve lives, while respecting what truly matters most to those affected.