Think Global, Act Local: Best Practices for Holistic Real-World Evidence

DATE

April 16, 2024

AUTHOR

Kristina Weber | Product Lead

In May of 2023, we hosted a 60-minute fireside chat with Paul Petraro on best practices for holistic Real-World Evidence. Paul works as an Executive Director and Global Heads in RWE at the Analytic Evidence Center at Boehringer Ingelheim, where he ensures the management and oversight of real-world studies along with developing RWE strategies. As a trained epidemiologist with a strong background in epidemiology methods and evidence, he is experienced in observational and experimental studies, fast authorization and risk management. Paul also has an in-depth knowledge of public and private epidemiologic resources.

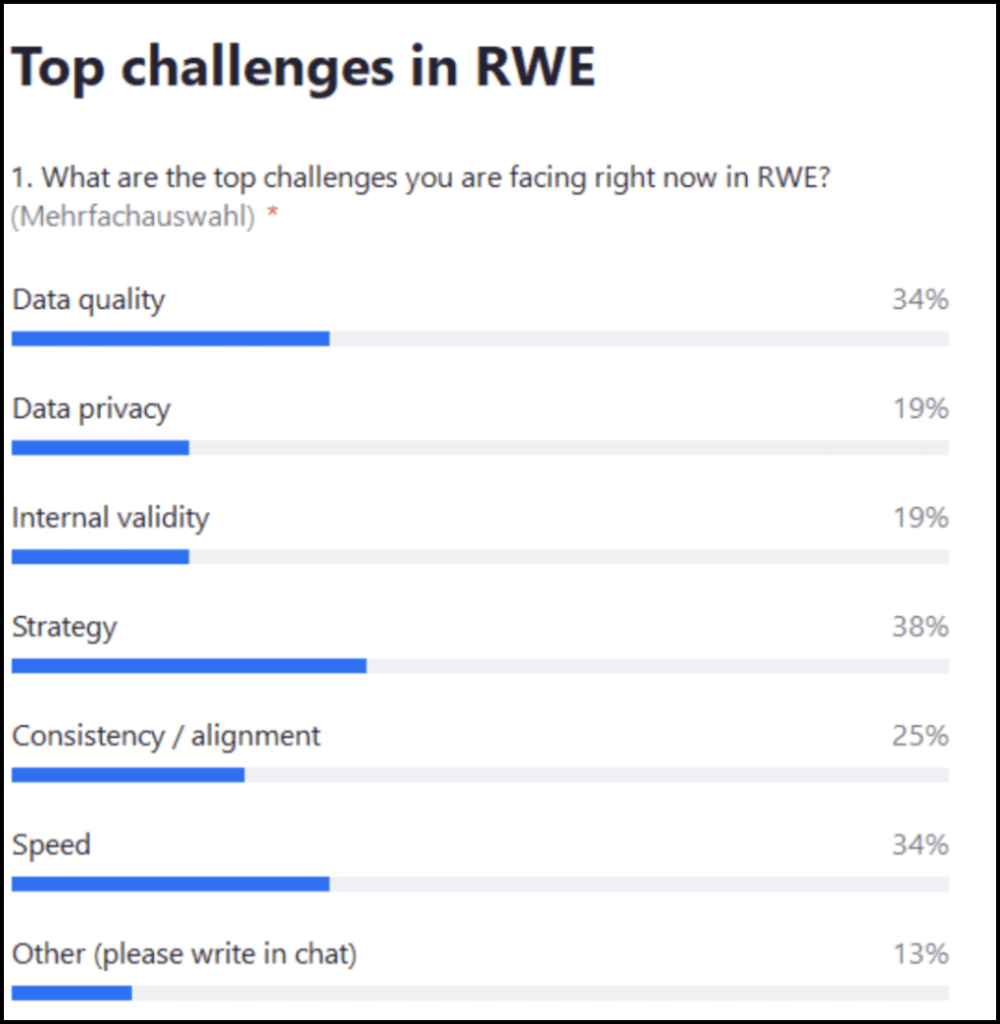

Our theme for this fireside chat was “Think Global, Act Local: Best Practices for Holistic Real-World Evidence”. We kicked the session off with a live audience poll:

Live audience poll: What are the top challenges for you facing right now in regard to RWE?

The top answer was strategy (38%), followed by speed and data quality (34% each), consistency alignment (25%) and also data privacy and internal validity 19%. A few people also mentioned other data extraction from patient files.

The next questions were directed at Paul.

What do you think about these results, which of these resonate with you and does anything surprise you in these answers?

Paul: I think all of them matter, and it’s definitely a good spread. I do agree that strategy should be top of the list. My second choice would be consistency and alignment. Those are the two that I think are the most important to this question. When it comes to evidence generation globally and locally, the biggest issue we have is consistency. So in terms of strategically thinking about evidence generation and how we work, we need an overarching global strategy.

There’s one path you are building towards, but that gets complicated very quickly because as we know, we live in a global environment. And on the local level, different countries have different health systems and different markets. All of that impacts local strategy, so the global and local strategy aren’t always going to align.

This is where consistency becomes really important: We start with that global strategy and we need to ensure that whatever evidence we’re generating is consistent. It may differ from local needs, but we can’t ignore those and must address them.

This can be challenging. So one of the things we should do once we have this strategy is to think about the questions we want to answer. This means that there’s a lot we can answer and a lot of evidence that we can generate from RWD, but is it really important to our customers? By customers I mean the whole spectrum, i.e. from our patients who are our most important customers, but also the health systems such as healthcare providers, payers and governments that we’re working with. All of them are going to have very different needs, very different questions that they would like answered.

So we need to figure out which ones are most important and how to prioritize which questions. How we go about that is very important.

How can we generate evidence in a holistic way?

Paul: Start early is one of my main messages across my organization. Anyone I speak to about generating holistic evidence, I will tell them to start extremely early.

If we think more traditionally, we usually go through the lifecycle of different study phases and don’t start thinking about RWE until Phase III, which is too late. Often, we’re not thinking about that early evidence along the patient journey with incidence prevalence etc.

The second thing that is really important is understanding the landscape. When we think about what evidence we need to generate, we need to know what data already exists. For example, think about publications: Is there any literature on our disease area? That will impact what we have to do as we move through the lifecycle.

Some key questions include:

- Do we need to generate new data or do we need to do something prospectively?

- Can we leverage existing data?

- What market are we going into?

- What’s available in the local landscape? For example, think about Germany versus Spain, France, China, the US, Mexico – what’s available there?

The answers may vary in terms of our customers, i.e. the health systems, patients and healthcare providers and what evidence they are seeking. For this, we need to know our organization’s strategy because it will impact everything along that pathway.

If the organization’s strategy is to focus on a specific subpopulation within a disease area, we must ensure that we’re being consistent with that population definition. After all, we don’t want to have five different definitions for non-small cell lung cancer or heart failure.

We may need that as we’re generating evidence, but we want to start with the same foundation. We know more and more organizations, groups, academics etc. and they’re all becoming increasingly savvy. The understanding of evidence generation of epidemiology and how the methods we leverage for the work is crucial here. When we generate this evidence, those questions are going to come to us.

People in the field will ask our local organizations such questions and they need to be ready to answer them. For example, this might be about why we defined certain populations differently, how we moved through evidence generation or why we defined it differently for two different instances. This is why I always come back to consistency as my underlying foundational path.

Are there some general best practices that you could share with us from the field of RWE?

Paul: First, you should start from that overarching strategy of your holistic evidence generation plans. We can’t think about trials and marketing authorization as one bucket and RWE and post marketing as another. It’s important to see this holistically from those early trials throughout the lifecycle and consider what we’re generating from a real-world and post-marketing perspective. We need to think from there and set some priorities.

We have a global evidence generation plan and we need to know what we’re focused on locally. We may not have the same priority list on a global versus a local level, but we should know what those priorities are. For example, let’s say our organization, which acts on a corporate/global level, should focus on 10 questions. The local organization, however, may see just 5 of those questions as important and only focus on those. Nevertheless, it’s important to be consistent and make sure we’re generating similar evidence across regions. Similar is a key word here because I completely understand that the definitions and methodology will likely be nuanced. But we need to start with that same foundation as we’re moving forward.

Bi-directional communication is a tough one, but it’s probably at the top of the list for best practices. It’s about understanding what the company is doing on a global level and what the local needs are. The local level needs to know exactly what global is doing and vice versa. This back-and-forth communication will ensure consistency and an understanding of what we’re doing.

The last bullet on alignment about implementation comes down to consistency. We want to understand while planning what evidence we’re going to generate and why there might be nuances. Circling back to that definition, if we’re trying to define heart failure differently in two studies (let’s say one in Japan and one in the U.S.), the definition is going to be slightly different. We need to understand why we’re doing that and align on why there’s a nuance there.

Now, you may ask why that even matters – one is Japan and one is the U.S. As we know, we live in a global world, so whatever is being done in Japan, the U.S. is going to know about it. Just because something’s done in a local market or in one country, it doesn’t mean that others are going to be unaware of that evidence generation.

A quick anecdote: I was working in the field in one of my previous roles and we were talking to a customer about evidence generation. There was a small abstract that was done in Europe and presented at a conference. The customer had seen that abstract and said “We saw this abstract and we want to replicate this study in our population in a health system in the U.S.” Now, we know that health systems work very differently across different regions. So if we replicated exactly that study from Italy in the U.S., it would look very different.

Therefore, we would need to be able to communicate key points such as “This is why it was done this way in Italy. If we want to do it in your health system in the U.S., this is why we have to do it differently.” The health systems, payers and local practitioners have their own data, so they can replicate a lot of the work that we’re doing on their data. We need to be able to understand what’s being generated and how.

So when those conversations occur, we can explain why there’s nuance and why the results look different. Obviously, most of our community is aware that there are going to be differences. But that doesn’t mean we’re not going to try and replicate things across the world.

Question: Given the various dictionaries used in the real-world, from SNOMED CT to ICD-10 etc., how do you envisage getting a uniform standard definition for a disease?

Paul: So I’m a big proponent of the common data model Odyssey. If you’re in Europe, there’s the initiative called Eden, where across Europe, I believe there are around 200 data partners already using the common data model. That’s really valuable and gets us into our consistency question because, with the use of common data model standardization technology, you can run analyses across very different data sources both in the variables the way they define things. You’re going to run into data where the results look very different, and we need to understand that and be able to communicate it.

Some of it may purely be a definition question and how that all translates into a common format but some of it may be underlying things about the population and about the way medicine is practiced differently there. For example, they may have guidelines that are different than in other countries. We need to be aware of that type of information going forward. Personally, I like OMOP (Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership) and I think it’s a good way to replicate things across the globe. There are other formats and ways we can leverage this.

Question: Concerning the strategy and consistency, how early in the development process does RWE get involved – pre-clinical or later?

Paul: That’s a tough one. I would like to see it early pre-clinical. But realistically, it’s probably Phase II. That’s the traditional way of thinking about RWE being used from the very beginning. Patient population incidence prevalence, i.e. understanding who the population you’re trying your molecule on is, is going after that at the very beginning.

But we need to make sure that’s understood within the organization that this is actually RWE at this stage. This is data that is coming in now, and we should be focused on it because sometimes we may push it to the side and say “Well, we’ll wait until we get to Phase II or III.”

To me, that’s too late because a lot of times our trial endpoints and the way our trials are designed show that the molecule works. That’s the goal of a Phase III study. Once we launch, we have to translate that to RWE. And the way we collect data, the way different health systems work, those endpoints might not be captured the same way. So we need to think about that early on.

There’s another question on the missing data problem, which is a bit unique because we’re not talking about missing data points such as a patient’s weight on every visit. Instead, we’re talking about specific populations, e.g. ethnic minorities or women. That’s a huge issue in the U.S. The FDA has added guidance on diversity in our trials. The way we focus on it currently is thinking about RWE, so if we go to RWD in a clinical setting, that’s going to capture diversity that may not be captured in clinical trials.

I disagree with that to some extent because if you look at the U.S. market in particular, there are people without health insurance. So if you don’t have insurance, you’re not going to the doctor or seeing healthcare providers, so you’re missing within that data. It doesn’t matter if we’re looking at RWD – you’re not seeking healthcare at all. There are many other underlying issues as to why this data is not being collected.

Therefore, we need to think of new ways of working, of how we engage those populations, ensuring that they’re comfortable participating in research and having their data collected. There’s way more history besides not going to the doctors as to why they’re not seeking care, not interested in clinical trials or don’t want their data captured.

With this, we’re going to the community level – it’s pure public health work and we have to start doing it much earlier to get people engaged and comfortable participating.

Question: Our recent patient survey showed that 76% of patients want to send and receive health-related information digitally, but still value personal contact and empathy from HCPs. What do you think this means for the future of clinical trials?

Paul: If I oversimplify it, hybrid is the term of the future because we tend to focus on what’s trending. With Covid, we saw a surge in decentralized trials where we focus on a totally new design, moving away from our traditional RCT.

And even with RWE generation and general evidence generation, we may start looking into new methods without thinking holistically. Therefore, I think it’s going to be much more hybrid and have a mix. I like pragmatic trials a lot because you have the whole spectrum there: From a truly pragmatic trial where you just randomized and leveraged RWD with no additional Within this, you’re probably doing a typical RCT with some enhanced data coming from the real world.

Those are the two extremes and a lot of it falls into the middle somewhere. You can get a lot from the RWD, but you may have to supplement it to some extent. That brings us to that second bullet on efficiency. The ideal is what works best for your specific research question. It’s not that you can’t fit the method to the question – you’re going to have your question that you’ll start with and then figure out the best way forward. It’s important not to force it either, because we’ve seen time and again that that’s where it ends up failing. Forcing a method or design just isn’t going to work.

Then I mentioned personalized therapies because I think that will continue to evolve. We need to think about new hybrid ways of getting answers to our research questions. Those populations are going to get very targeted and it’s going to be difficult to run a traditional trial, whether it’s real-world or a clinical trial.

Question: How do you ensure enriched quality data?

Paul: I actually start from the patient or the end user who is going to use our molecules or technologies. So we need to think about how to reduce their burden. There are many reasons why participation may be low in traditional trials, one of the most common ones being time. People are busy going to sites, filling out questionnaires etc. So how do we reduce the patient’s burden as much as possible while getting the best quality data?

We’re moving to a place where that’s becoming easier and technology is key there. For example, linkage tokenization is big in the U.S. right now, i.e. the ability to link disparate data sources to enhance that data. I believe that will grow dramatically and it will become increasingly easy to do so.

The most important piece out of everything we do going forward has to be transparency and that’s transparency across the board. We tend to think about transparency from a data perspective and what we’re submitting to the FDA or reporting back to investigators, sites, authorities, Health Systems etc.

But the one piece of transparency you don’t hear about is whether we’re ensuring that our patients are getting the information back from our studies. I think that comes down to our abilities to leverage technology and data because people understand how and why you’re going to use their data.

At the end of the day, all the data we’re using is not the health system’s data or the payer’s data. It’s the patients’ data. So if they’re aware, some of these will become a lot easier.

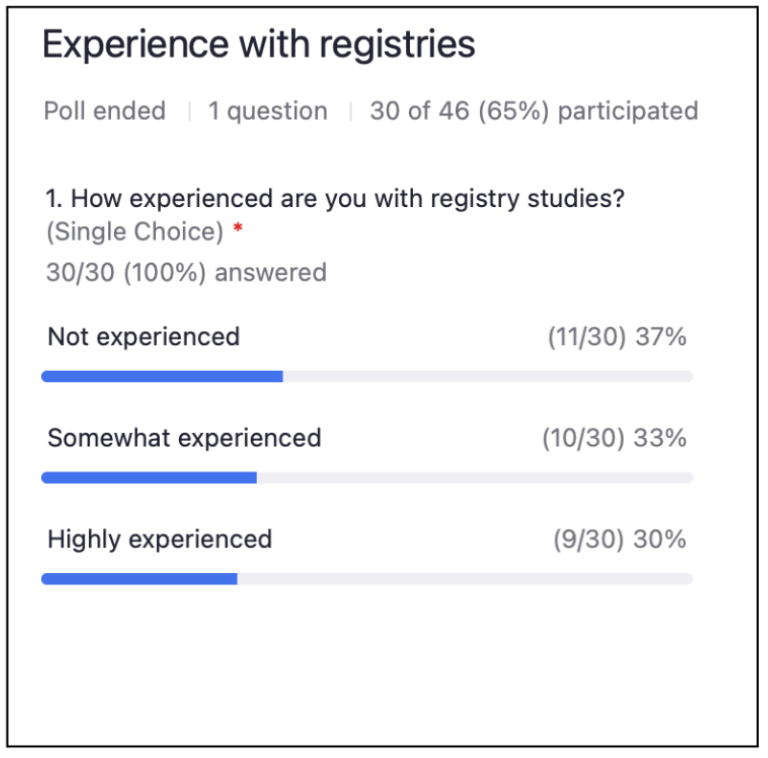

Live audience poll: How experienced are you with clinical registries?

Paul: The way I see linkage working is that personal information (such as name, date of birth, address, social security number, government ID) is used to create an encrypted code behind the firewall. And that code is then considered a token or a way to link data. This is done in various data sources. By using software, you can unencrypt those codes and run overlaps to see where the linkage has occurred.

Once that’s done, if you are going to leverage that data for research, it undergoes a certification for HIPAA compliance which is the equivalent of GDPR in Europe. So if it undergoes that, it maintains its anonymity and you can leverage that data to do research in Europe. Once you create that encrypted code where in HIPAA and in the U.S that encrypted code is not considered personal information outside the U.S., that is considered personal information.

This is becoming increasingly common in the UK too, and I’m also hearing plans about expanding across Europe. That token is personal information, so it would stay behind the firewall and when data is linked and pseudonymized (which is different from what we consider anonymized in the U.S.), you would be able to leverage that for real-world work.

Now, as for the second question on what role patient consent plays in RWE when it comes to tokenization: In my organization, that is not just a nice to have, but a requirement. In the U.S, you actually do not need to consent the patient to use their data for RWE work.

So anyone we want to leverage tokenization for or whatever we want them consented for, I think going forward we should be consenting patients even for things such as RWE generation. It increases the transparency if a patient agrees to participate in this and we could share what we’re generating in the results and how this fits into their personal data background. In my opinion, this will increase participation and really help Public Health in general. Not because patients will be much closer to their data, but because they’ll see “Oh, this research was done, it says XYZ and that’s how that fits into my profile.” With technology, we should be able to have consent for this type of work as well.

Question: What do you think about registries?

Paul: I think they are sometimes antiquated when considered in the traditional, prospective new data collection. In one of my earlier industry jobs, I was working in a rare disease space where there was a need for data. We didn’t think it was available in the real world so we decided to do a prospective registry. So first, we figured out the questions we were going to ask patients. I received a PDF of the questions to review before we went live with the registry and when I opened it, it contained 67 pages of questions. Now, if we’re thinking about patient burden and how this fits in, what’s the value to the patient to fill in all of this information on a regular basis? And how will we leverage that data?

I definitely buy into the idea of “fit for purpose”. Nevertheless, I think we need to go back to a hybrid model. It depends on what you’re looking for and where prospective data is needed. For example, we have wearables, medical records, apps, claims etc. So there are many sources we could try leveraging and then just supplement what we need to add to that registry. I’ll throw that in air quotes because we need to rethink not the term but how we define it.

Many people still think about registry in the traditional sense which I believe we’re gradually moving away from. But there’s plenty of technology out there that helps us leverage a patient’s real world data, supplement it with their wearables, for example, and then ask them 3-5 questions instead of 50 questions. That’s the future of holistic real-world evidence in my opinion.

Question: Patient retention in RWE is notoriously low in post-market phases. What can we do to improve this?

Paul: Some newer organizations out there use a payment model. We’re not paying for the data perspective per se, but for example, patients can receive rewards if they participate or submit their data. That being said, we do see this as a commodity which we leverage all the time.

I think that will also help us to some extent in terms of recruitment. There’s still going to be transparency planning and the value-add. I don’t mean value-add from a patient’s perspective. What does submitting their data and answering questions do for them? They need to be able to see that, whether it’s the outcome of the study, the results being published, them learning that there’s a new treatment available or if they’re adherent on their drug etc. As a result, the drug will be that much more effective. So we need to share that with patients and help them see what’s actually happening. We shouldn’t just be taking their data and then working with it to create a nice publication.

Question: What about automated data extraction from electronic patient files, consent ethics approval etc.?

Paul: That’s one place where I see RWD or clinical data being crucial and where an EDC takes RWD and inputs it into the electronic format for a clinical trial. Before I joined the industry, I actually sat on the Ethics Committee of a hospital I was working at. Those are extremely valuable because they’re looking at how this is being used, ensuring patient safety and ensuring that we’re being ethical. That’s necessary and should never go away. As for consent and ethical approvals, we need those regardless of how we’re getting the data.

Thank you Paul for the insightful fireside chat! To watch the full session on demand, click here.